The history of the empire does not begin with the imperialism of the nineteenth century or with the 16th-century colonies of European nations. No, across the nearly 5,000 years of recorded human history, the Akkadian Empire of ancient Mesopotamia was truly the first multinational political entity on Earth, the first political entity to dominate independent city-states militarily and maintain consolidated, unified control through repeated military campaigns.

Conquest has been a recurring theme in human history in much the same way imperialism, the systematic process of establishing and maintaining an empire, has reemerged across various civilizations. Certainly, the rise and fall of empires have led in many ways to the proliferation of progress. By establishing infrastructure, guarding trade routes, and enforcing uniform systems, empires frequently promote trade and economic expansion within their borders.

The Akkadians, the Assyrians, the Athenians, and most empires throughout history have been primarily driven by trade, political ambition, resource control, and the desire for prestige and power. This bestial desire for power has, in many instances, contributed to the inevitable decline of many empires throughout human history. The view that the United States is an empire in decline has developed significantly in recent years, but to call the U.S. an empire is simply an understatement of its sheer global dominance. It was Sargon of Akkad, the king of the Akkadian Empire, who once wrote that he had conquered “the four corners of the universe.” However, there has never been a political state within recorded human history with a more prominent global surveillance apparatus, economic influence, and international military might than the U.S. Empire.

From a technological capacity alone, virtually nothing prevents the US state from establishing absolute surveillance where all American citizens’ communications, movements, and activities are tracked. With origins in wartime monitoring and censorship, the U.S. government has been conducting state surveillance for more than a century. Federal law enforcement and intelligence organizations gradually institutionalized early forms of surveillance, such as keeping an eye on international communications. It has used various strategies and programs to carry out these extensive monitoring operations at the state and federal levels. This includes focusing on foreign and domestic targets, with PRISM and Section 702 programs providing a significant portion of the data. In addition to permitting “backdoor searches” of communications belonging to U.S. persons that are part of this gathered data, Section 702 allows the warrantless acquisition of communications from foreign targets. The FBI alone conducted more than 200,000 of these searches as recently as 2022.

PRISM was publicly revealed on 6 June 2013, after Edward Snowden leaked classified documents about the program to The Washington Post and The Guardian. The Protect America Act of 2007 under President Bush and the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, which immunized private companies that voluntarily assisted with US intelligence collection and was extended by Congress under President Obama in 2012, made it possible for the PRISM special source operation system to collect the private data of millions of Americans without warrants or criminal arraignments.

The US has a long and extensive history of mass surveillance, going as far back as the early 20th century. This practice began with wartime monitoring and censorship, especially during and after World Wars I and II. Programs like Project SHAMROCK and COINTELPRO continued this mass surveillance into the Cold War era, and the expansion of federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies further institutionalized it. Following 9/11, the practice became much more widespread, with the PATRIOT Act of 2001 giving the government more power to monitor email and phone communications.

While much has been said about alleged fraud and waste within the US administrative state, scarce contention has been brought against America’s massive military budget. On January 17, 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower delivered a farewell address on live television from the Oval Office in the White House. Given that he had previously served the country as the military commander of the Allied forces during World War II, his remarks during the farewell address to the American people were especially noteworthy. American industry successfully converted into defense production as the demand became more critical. However, Eisenhower warned that a permanent armaments industry of colossal proportions was beginning to emerge.

The federal government has spent over half of its tax revenue on past, present, and future military actions since the conclusion of World War II. It is the federal government’s most significant public investment, with the Pentagon budget nearly reaching $1 trillion alone. Prior to production, military equipment is sold with the assurance that considerable cost overruns will, hopefully, eventually be addressed. With the biggest increases linked to ongoing conflicts, such as a 40% increase in revenues for Russian companies supplying Moscow’s war on Ukraine and record sales for Israeli firms producing weapons used in the country’s ruthless war on Gaza, the world’s top 100 companies that produce arms and military services saw their revenues total $632 billion in 2023, a 4.2% increase over the previous year.

To protect its commercial and geopolitical interests, the US has utilized its military might and clandestine activities to topple or support regimes across the world throughout its history. Attacks against and evictions from independent tribal communities in North America marked the beginning of US meddling in foreign governance. When the United States destroyed the Hawaiian Kingdom and seized its islands in the 1890s, this brand of imperialist activity, driven by the notion of Manifest Destiny, expanded abroad.

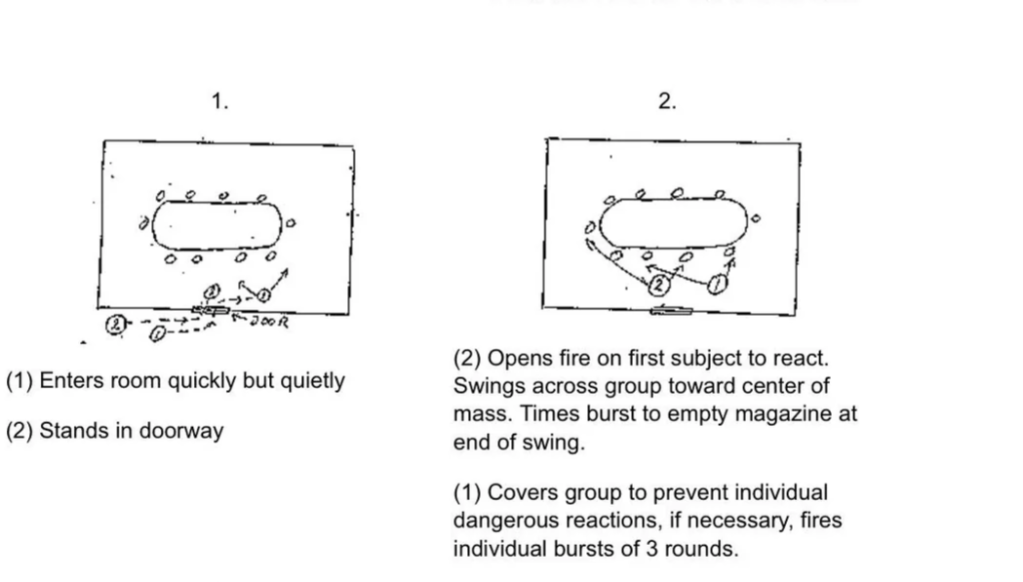

The US has often meddled in other nations’ administrations as it expanded its empire, none more prominently than those in Latin America, which has long been utilized as the government’s backyard playground. During the Guatemalan Genocide, the mass killing of the Maya Indigenous people had been carried out by the successive Guatemalan military governments that first took power after the CIA-instigated 1954 coup d’état, utilizing training obtained via the CIA Study of Assassination. This 19-page manual offered detailed descriptions regarding the art of political killing, including procedures, instruments, and implementation of assassination.

During the Cold War, the extent and breadth of covert operations, notably those conducted by the CIA, increased significantly. These activities included everything from psychological warfare to insurgency and counter-insurgency efforts. In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the CIA established a system of undisclosed black site prisons throughout the world in which it secretly detained at least 119 Muslim men and tortured at least 39. Of the at least 780 Muslim men and boys the US has detained in Guantánamo since January 11, 2002, the US military continues to hold 39 of them, 27 of whom are not facing criminal charges. Waterboarding, sexual humiliation and assault, physical abuse, and sleep deprivation were among the torture these prisoners suffered. Former inmates continue to suffer from physical and psychological trauma as a result of their treatment at Guantánamo Bay, and a 2014 U.S. Senate intelligence investigation concluded that the torture program failed to achieve its purported objective of gathering military intelligence.

Many people believed that the path of human history had changed irrevocably after September 11th. It was impossible to predict how different our world would become, but 24 years later, the most enduring impact may have been the irreversible damage to the national psyche, which, in many ways, has led us to the reactionary expansion of the state. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is a relatively new federal agency, as it was established along with the TSA as a direct response to 9/11. The scale of ICE’s law enforcement capabilities has been dramatically increased recently by collaborating with local law enforcement organizations nationwide. This arrangement has enabled local officers to perform specific immigration enforcement tasks under ICE’s strict supervision and guidance.

Reports of noncitizens unexpectedly being detained by ICE have dominated headlines, especially those concerning noncitizens living in the country on lawful permanent residency status. Mahmoud Khalil, a recent Columbia University graduate and lawful permanent citizen, was arrested on March 8, 2025, after being first held in New Jersey and then sent to a migrant detainment facility in Louisiana. He remains there as he contests his detention and the immigration judge’s ruling on April 11 that permits his deportation. In response to questions regarding the reasons behind activist Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest by immigration officials, the Department of Homeland Security released a two-page memo from Secretary of State Marco Rubio accusing the graduate student from Columbia University of participating in “antisemitic protests and disruptive activities.” According to his attorneys, that memo is at the heart of the government’s case against Khalil.

While the memo makes no criminal accusations against Khalil, Rubio writes that his prolonged stay in the United States would have “potentially serious adverse foreign consequences and compromise a compelling U.S. foreign policy interest.” One might wonder how a federal government agency can legally abduct and indefinitely detain a lawful permanent resident of the United States based solely on preserving its own geopolitical interests. Still, one can look no further than the legacy of the Cold War. In 1952, the US Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which permits ICE officers to legally detain and interrogate any individual they believe to be a non-citizen regarding their right to live or remain in the US. The Immigration and Nationality Act also states that noncitizens may be deported if the Secretary of State believes their actions “would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.”

The US has the world’s highest immigrant incarceration rate, with over 35,000 people imprisoned daily for administrative hearings to decide deportation. Louisiana, the second-largest state for immigrant detention behind Texas, currently detains over 6,000 people, including asylum seekers and long-term residents. The late 2010s saw a surge in immigrant detention in Louisiana, primarily benefiting private prison companies who operate eight of the state’s immigration jails, profiting from abuses.

ICE and DHS hold tens of thousands of people daily in private prisons, local jails, and federal facilities, mostly in rural America. Individuals are detained in immigration to allow the federal government to process them for admission or removal through the civil immigration system, rather than as punishment for a crime. Immigration jails’ harsh conditions isolate immigrants from legal assistance, serving the government’s goal of discouraging further immigration. The US government currently holds over 6,000 immigrants in nine jails in Louisiana’s northern region. Immigration detention is considered civil confinement under US law. Civil detention, unlike criminal confinement, cannot include punitive conditions. In reality, NOLA ICE officials use immigration detention centers as punitive prisons to break the will and spirit of detained individuals.

ICE jails in northern Louisiana are repurposed prisons that previously housed individuals awaiting trial or serving sentences. The area is still surrounded by barbed wire fencing and gated access. Detainees in NOLA ICE jails who have not been charged or convicted of a crime share cells, jumpsuits, and freedom restrictions with criminals. However, detained immigrants do not have the same protections as those in criminal custody, including the right to counsel under the Constitution.

NOLA ICE officials restrict detainees’ movements, detaining them in tight places and holding them in chains for extended hours. Detained individuals are not allowed to access medical services or the law library without the presence of a guard. Access to outdoor activities may be limited to one hour per day or denied for up to ten days. Guards handcuff individuals during transfers between NOLA ICE facilities, transportation outside the jail, and to solitary detention. Officials utilize “five-point restraints,” which are shackles connected by metal chains to the wrists, waist, and ankles.

These carceral conditions of imprisonment have caused considerable bodily and psychological injury to detainees, with one such case being at the Central Louisiana ICE Processing Center. CLIPC authorities used five-point shackles to cover open wounds on the ankles of a man with Type II diabetes. The patient was referred to an endocrinologist for off-site treatment, and officials were instructed not to cuff his ankles. ICE canceled the man’s appointment, denying him daily wound debridement and care for five days. Detainees at Pine Prairie, transferred from the US-Mexico border to Louisiana, were shackled in five-point shackles for 26 hours, prohibiting them from using the restroom, eating, or drinking, which resulted in several infected slashes on their wrists and legs.

The US government has various oversight mechanisms to monitor and report abusive conditions in NOLA ICE jails. These include internal inspections by ICE, the Department of Homeland Security, executive agency watchdogs, and congressional investigations. However, these processes have repeatedly failed to address and prevent systemic abuse and deplorable conditions in NOLA ICE jails, and several agencies under the Department of Homeland Security lack the necessary independence to hold abusers accountable.

The question we should ask ourselves, dear reader, is whether or not we should allow the US Federal Government to operate with absolute impunity. If they are willing to violate the constitutional rights of non-citizens, whether they are lawful residents or undocumented immigrants, what truly legitimate self-correcting mechanism would be in place to protect American citizens? These infernal beast systems – mass surveillance and incarceration, covert state operations, and the ever-growing influence of the military-industrial complex- all have proven themselves to be everlasting symptoms of the disease of empire. But what drives an empire? The acquisition of centralized power, dominance over weaker states, resource extraction, and the pursuit of enforcing peace by establishing a multinational hegemony. By engaging in a vast transgression against the sovereignty of humanity, the empire expands its reach through the armed hands of cultural disintegration and assimilation, from the colonial projects of the Spanish conquistadors to the very first genocides of the 20th century in Namibia and Armenia. The empire cannot function without the beast systems.